Quality knowledge from an old master

The lucky among us can point to a teacher, mentor or writer who made us see the world in a different way.

Val Feigenbaum was that person for me. He died recently aged 94.

I distinctly remember the moment when Feigenbaum changed my understanding of quality - and of manufacturing as a whole. I was reading an article of his that talked about the popular belief that quality was a cost to a business. He believed that this was fundamentally wrong. Feigenbaum argued that “quality and cost are a sum, not a difference – complementary, not conflicting objectives”. He demonstrated that there was a (significant) cost of poor quality and how focussing on quality actually reduces costs.

Total quality costs

Feignbaum said that quality costs occurred in two ways. The first were the costs of control, made up of preventing costs (such as training and systems development) and appraisal costs (inspection and auditing, for example). The second group of costs were the costs of the failure of control. These costs are made up of internal failure costs (which come about through catching and discarding faulty items) and external failure costs (which arise from defects that actually reach customers).

By categorising quality costs in this way, such costs can be measured, analysed, budgeted for and predicted. They can also be efficiently and properly dealt with.

Feigenbaum went even further. He argued that not only were quality costs invisible, they were often bigger than the bottom-line profit achieved for particular products – meaning that some products weren’t actually profitable at all.

Further, for some businesses, these costs were so high that they negatively affected their competitive position.

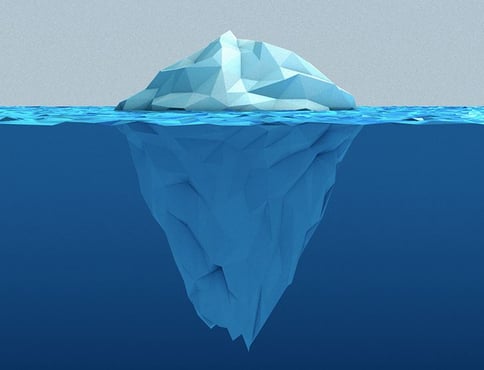

The hidden factory

Then Feigenbaum hit me with the humdinger – that inside every factory is a hidden factory. The role of this hidden factory is to fix up all the mistakes. It is a factory that loses money within the factory that makes the products.

I couldn’t believe it. It was as if Feigenbaum had given me a new, powerful set of glasses that allowed me to clearly see what was actually going on.

Feigenbaum’s bottom line was that whatever you do to make quality better, makes everything else better too. He believed that quality is the most cost-effective, least-capital intensive route to productivity. That’s an incredibly powerful idea.

What sort of quality professional would I be if I hadn’t read – and adopted - Feigenbaum’s ideas? He very clearly showed me that quality has to be the mindset of every single person working for an organisation. He gave me a new way of seeing the things I was looking at every day.

If we are going to continue enjoying work, I firmly believe that we must keep learning and growing. Not only does it keep things interesting, it also allows us to continue to improve (kaizen!) both professionally and personally. Deming, Juran and Feigenbaum continued to work and develop their ideas well into their 80s and 90s. If people at the very top of their field can do this, then the rest of us have plenty of scope to keep learning and growing.

We can’t rely on luck to bring these wise people into our lives. Very often we have to seek them out. We have to take a chance on picking up that book. We have to be brave enough to put our preconceptions to one side and listen with an open mind. We have to connect things that wouldn’t usually go together. The internet makes this so easy. We really have no excuses for laziness.

The takeaway

Take a look at some Ted Talks. Read the books and/or blogs of people like Seth Godin, Mark Suster, Michael Stelzner. Seek out people who aren’t in your comfort zone and tune in for a while. Play the game of seeing how their underlying message or philosophy might relate to your work.

But most of all, don’t forget to revisit the old masters like Val Feigenbaum. He really was an inspiration.

.png?width=200&height=51&name=image%20(2).png)